The phrase was originally formatted by a Roman author while deploring the declining heroism of Romans after the almighty empire ceased to exist. Consequently, the government kept the Roman populace happy by distributing free food and staging huge spectacles.

Ironically, the Pakistan Television Corporation has become somewhat an exemplification unto the phrase itself. Amidst all the glory and sanctification, the government-owned network was only a sanctuary for its performers up until they could act and continue their job as a crowd pleaser; at its end which they were disposed of and never heard from again.

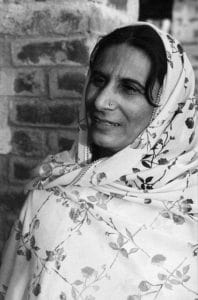

The 90’s was a golden era for the PTV; spectators nationwide were increasing and growing in numbers and shows that broke all ratings, casted a popular vote from the audiences who were glued to their sets, their absences resonating a hush over the streets at night. Amongst those shows was an all-time favorite Ainak Wala Jin, which portrayed a hysterically sinister character by the name of Bil Batori, played by none other than the very talented Nusrat Ara.

Turned 65, the actress was found begging at the shrine of Data Ali Hajveri for food and money, where after collapsing from starvation and exhaustion, she was brought to Sir Ganga Ram Hospital. The marvel television entertainer’s career came to an end with the termination of the show, and she was unable to locate work anywhere else.

“Is it not cruel that after four decades of serving the Pakistani entertainment industry, I don’t have a roof over my head and the government is not even bothered about that? I am a proud Pakistani and don’t want to complain. But it’s about time that the government reflects upon how it’s looking after its artists and learns from what is happening around the world.” – Nusrat Ara, The Express Tribune.

Other actors like Roohi Bano and Munna Lahori were found in similar situations after facing the aftermath of acute poverty, having no jobs as a straw to grasp at.

It is grimly unfortunate how we as a nation who consistently bewails and laments over the lack of national assets, are resultantly the reason behind their depreciation and downfall for we fail to value and support them as required.

Perhaps on account of the uproar and media exposure created by the discovery of these thespians, the Punjab government finally announced the launch of ‘Artist Khidmat Card Scheme’ on the 23rd of March, 2017 where an allotted amount of funds would transferred to the accounts of a group of notable artists (if they fit the bill of a set criteria) every month.

But the debate remains as to whether the card fulfills the idea of corporate social responsibility. Increasing privatization has resulted in a record number of productions starring Pakistanis in documentaries, television serials and movies. The concept of patronage can either attract or repel people from the entertainment industry, since it can often be followed by inefficiency, as well as the test of time as opposed to competition.

Although the scheme is underway as a work in progress, it is hoped that unlike the many previously run strategies, it turns out to be successful and beneficial. Pakistan is already a victim to several financial constraints and corruption, where a budget cut in nearly every sector has become a norm practiced annually. The label of doubt has already been attached over the maintenance of the programme by the government and its continuation at all in the future or at the very least, with the current allocated money.

Moreover, the government has asked artists to step forward and apply for the card online as means of financial assistance but there may be several such people who are unsound of mind or health or void of any technical resource availability to be able to this. Similarly, the scheme only covers citizens possessing Punjab domicile which seems to be an unfair distinction. This brings us to another ruthless prospect which indicates that the Pakistani government has a very poor track record of the identification of our artists.